Image: © David de Rueda, Exploration of the abandoned space shuttles in Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan, https://www.davidderueda.com/en/baikonur/

ABSTRACT

This article argues that urban exploration (urbex) should be understood not merely as leisure or subculture but as a living, grassroots form of cultural heritage. Drawing on critical heritage studies, it reframes heritage as a social practice—performed, negotiated, and often contested—rather than a fixed set of canonized objects. Using interdisciplinary literature and case-led discussion, the paper maps urbex’s defining features (illegality/ inaccessibility, sensory intensity, narrativity, documentation ethics) and situates them historically from psychogeography to contemporary “space hacking.” It outlines ethical tensions around risk, trespass, commodification, and location disclosure, and shows how community norms (“take nothing but pictures”) mitigate harm. Two ideal-type explorer profiles—performative and communicative—illuminate how experience-making, documentation, and informal archiving produce bottom-up memory-work. The article links urbex to concepts such as heterotopia, rhizome, entropic/alternative heritage, and negative heritage to explain how explorers ascribe value to abandoned, post-industrial, or otherwise excluded places without formal protection. Finally, it proposes future research on gendered/accessibility dynamics, cross-cultural ruin imaginaries, and the role of VR/3D/sound archives in documenting ephemeral sites. Urbex emerges as a culturally significant practice that reorients heritage from preservation of static objects toward situated, sensory, and participatory making of place and meaning.

Keywords: urban exploration; urbex; critical heritage studies; alternative/entropic heritage; psychogeography; heterotopia; documentation ethics; post-industrial ruins; memory-work; sensory heritage.

“Exploration serves no purpose when its results remain obscure… It was only the advent of this publishing tradition that transformed the desultory trespasses of scattered souls into a coherent movement.” — Jinx Magazine, “Psychopathology and the Hidden City.”

Urban exploration (urbex) is a phenomenon that exceeds simple categories of recreation, tourism, or subculture, becoming a multi-layered way of experiencing, documenting, and interpreting spaces that are abandoned, forgotten, or excluded from the dominant cultural circuit. The aim of this article is to present urbex as a form of living cultural heritage—unofficial yet intensely lived, documented, and co-created from the bottom up. Through sensory exploration, narrative-making, artistic actions, and a critical approach to institutional models of protection, this practice reveals new ways of participating in culture and redefines the notion of heritage in the spirit of critical heritage studies. Urbex not only records transience and decay, but also becomes an active way of assigning meanings to places erased from official memory—an aesthetic, social, and political act.

An analysis of the available literature shows that urbex has already attracted wide interest from researchers. Importantly, reflection on the phenomenon is distinctly interdisciplinary. It has been written about by sociologists, architects, urban planners, cultural studies scholars, ethnographers, philosophers, as well as artists and explorers themselves. From these diverse perspectives, one consistent conclusion emerges—urbex is an extraordinarily capacious phenomenon that reveals its cultural potential as a form of grassroots heritage in practice. It is a subculture and an alternative form of association; a practice of crossing boundaries—both physical and symbolic; a way of working with memory, documentation, archiving, and generating one’s own narratives and artistic creations. Urbex is also a space for experimenting with identity, for making place through experience, and often an effect of urban policies that tangibly impact local communities. In short—it is not simply aimless wandering out of boredom through abandoned buildings with a flashlight wearing in cargo pants.:)

URBEX — DEFINITION, FEATURES, AND TYPOLOGY

In its most basic sense, urbex is “a movement aligned with the trend of guerrilla-cultural activity by residents of cities and urbanized areas. Urban exploring consists of visiting human habitats from the perspective of places that the general public should not, or does not wish to—see.These can be abandoned churches, monasteries, and cemeteries; sewers, catacombs, and tunnels; shafts and mines; hospitals and sanatoriums; old schools and boarding houses; factories and industrial plants; airports and derelict ships; amusement parks and resorts; bunkers, fortifications, and military sites; as well as deserted palaces, private houses, and villas. In short—the movement targets everything that, for various reasons, no longer attracts the interest of the broader public. Such places are characterized by inaccessibility, illegality, sensory intensity, subcultural ethics of exploration, the temporariness of communities, a focus on documentation, narrativity, and the creation of grassroots histories of place.” As Kevin Bingham notes, urbex also has a heterotopic character: a space of “otherness” in every possible sense of the word.

Urban exploration also has historical roots. As early as 1793, Philibert Aspairt, in search of lost corridors, entered the Paris catacombs and disappeared; his body was found only 11 years later. The 20th century saw new forms of urban drifting—in the 1960s, the concept of situationist psychogeography was born. Introduced by Guy Debord and the Situationist International, it described the influence of urban space on individuals’ emotions and actions. Psychogeography encouraged intuitive exploration of the city beyond beaten paths to regain authentic contact with space. In the 1980s, MIT students inaugurated traditions known as tunnel hacking and roof hacking—forms of exploring technical systems and the roofs of institutional buildings.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari introduced the philosophical concept of the rhizome, which concisely and aptly describes urbex’s basic assumptions and spirit. Biologically, a rhizome is a horizontally spreading structure that grows in many directions without hierarchy or center. The authors applied the concept socially and philosophically to describe formations that develop non-centrally and in many directions at once, in opposition to the classic branching tree hierarchy. This framing perfectly captures urbex’s nature for several reasons:

- the subculture lacks any central leadership or defined direction,

- urbex develops spontaneously and heterogeneously—fluidly connecting with other practices such as rooftopping, graffiti, parkour, free climbing, or even squatting, and appears in variants like tunnel or roof hacking,

- it is a network of actions and practices that constantly grows, creating new offshoots and hybrids—without a center, without a plan, yet with a strong sense of community and purpose.

What, then, is urbex today? Certainly more than a form of urban adventure. It is a space of political, social, and artistic narratives. Though sometimes controversial—often equated with vandalism—such simplifications fail to capture its complexity. Like many alternative forms of activity, urbex deserves analysis rather than being reduced to marginal incidents.

Urbex also has a darker side: the mute presence of ruins, hundreds of thousands of which are scattered around the world, often as traces of natural or social disasters. In many cases these spaces are still inhabited by communities that remain invisible within local narratives of power and development. An example is Warsaw’s Kamionek—despite residents’ opposition, the area was consumed by the developer Dom Development, where blocks of flats were built.

ETHICS AND LIMITS OF EXPLORATION

The issue of legality in urbex cannot be ignored—it is an inseparable aspect of the practice. Many sites are on private land, sometimes still guarded, and the laws of most countries are fairly consistent here. Moving through such spaces without permission involves a range of risks—including legal and personal risks borne by the explorer. The most important include:

- illegality of access and site protection

- personal (including physical) risk tied to exploring unknown spaces,

- the danger of commodification (turning practices or experiences into consumer goods) and the spectacularization of exploration (shifting emphasis from experience to spectacle, e.g., selfies atop high-rise buildings),

- marginalization and exclusion of certain social groups by gender and physical ability,

- dilemmas related to publishing locations and responsibility for potential damage.

Despite these hazards, the urbex community has developed its own ethical code to minimize negative impacts. Frequently cited rules include:

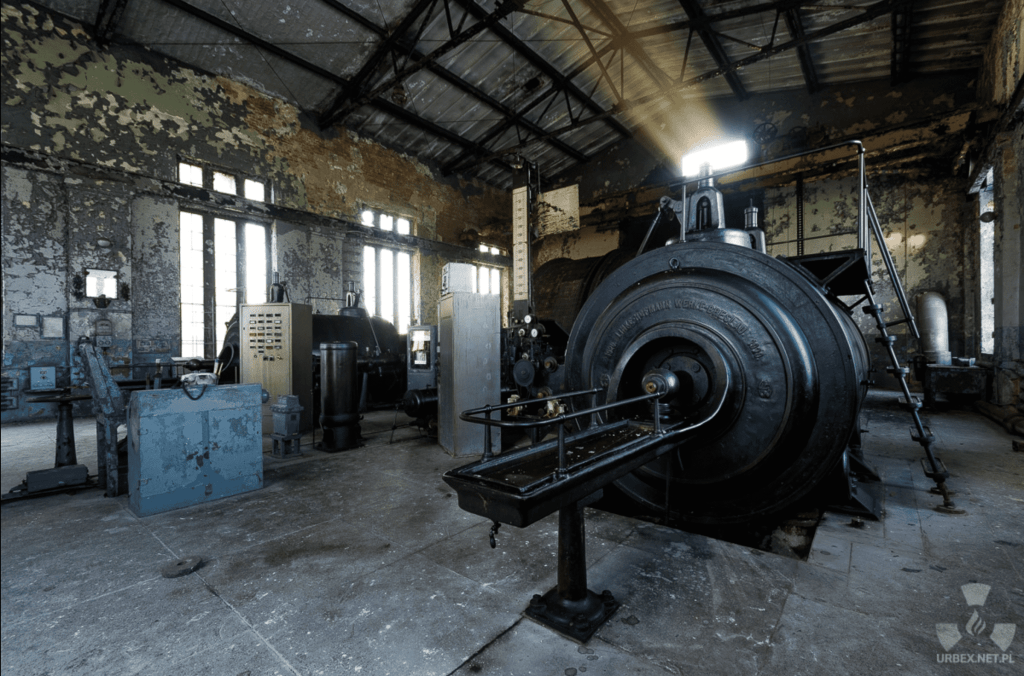

- “Take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints” (see Fig.1)—do not take anything besides photographs and leave only footprints.

- “Explore, respect, protect”—act consciously, respecting the site and its history.

- Avoid publishing precise locations to prevent vandalism, looting, or the “Instagram effect”.

- Promote exploration grounded in knowledge and respect for the space, its past, and the local community.

Commercialization attempts are also an intriguing thread. Consider the Ukrainian Zona (Chernobyl/Pripyat), Berlin and New York undergrounds, or Kazakhstan’s opening to tourism to places like deserts where nuclear tests were once conducted. This form of experiencing “difficult” spaces raises serious ethical questions.

Is disaster tourism merely for edge-seekers and thrill-hunters? Or can it also be a sphere for amateur-researchers with documentary, artistic, or identity aims? Here again the rhizome concept proves accurate: as a socio-cultural phenomenon, urbex grows organically, multi-directionally, and non-linearly—moving far beyond original forms of action and continually creating new offshoots, from subcultural exploration through grassroots documentation to commercial experiences of ruins and disaster sites.

URBEX IN AN URBAN PLANNING PERSPECTIVE

Having discussed urbex’s ethical and legal issues, we should ask how exploring abandoned places fits broader urban processes and challenges dominant spatial models. Although urban exploration suggests a tight link with the city, in practice urbex crosses metropolitan borders. Variants appear such as rurex—exploring places far from urban centers. Baikonur, for instance, requires near-expeditionary preparation to reach, showing that urbex can also be a form of peripheral and post-apocalyptic landscape exploration.

Key phenomena with social, political, and urban dimensions include:

(1) space hacking—breaking spatial control as a critique of over-regulation via direct reclamation;

(2) the surveillance society and spatial control—amid permanent monitoring (CCTV, digital IDs, location logs), urbex can be read as resistance to surveillance and the disciplining of urban space;

(3) situationist psychogeography—urbex as a contemporary form of dérive, intuitively drifting through the city against its functional divisions;

(4) ghost cities—urbex gains new meaning amid global urbanization processes, e.g., China’s modern yet deserted cities formed by spatial speculation and planning errors—ruins of the future born not of decay but of excess, redundancy, and systemic exclusion.

Understanding how urbex responds to contemporary urbanization and spatial control allows us to better grasp its social and cultural significance: not just adventure or subcultural identity seeking but also a critical practice—commentary on mechanisms of urbanization, spatial governance, and exclusion. To capture the phenomenon fully, we must also consider the explorer’s individual experience and the building of communities and relations around these activities.

THE EXPERIENCE OF URBEX AND COMMUNITIES

(Trasnlation: We go where we are not allowed)

Sociology coined the notion of accounts—testimonies, relations, narratives through which individuals give meaning to events and build identities. As Debra Orbuch notes, it is through such narratives that individuals order their experiences and situate themselves in the social world. Urbex, as a space of individual narratives—often also historically or culturally grounded—lends itself to analyzing how these stories are formed and how identity is defined in relation to the places visited. Why do people do urbex at all, and how is it experienced?

- Urbex as a bodily, sensory experience of space—encompassing all sensory and emotional states: from a sense of danger and excitement about the unknown, through experiencing the multi-temporality of places, reflecting on the authenticity of experience and a critique of capitalism, to perceiving sounds and silence (as opposed to the dominance of visuality). Sounds can carry memory, and engaging multiple senses deepens place reception.

- Heterotopic communities: ephemerality and performativity. Kevin Bingham distinguishes two explorer types:

- Performatives—adventure-seekers who craft their own narratives yet act ethically: they neither vandalize nor reveal locations. Their stance aligns with:

- entropic heritage—accepting natural decay as cultural value (DeSilvey);

- alternative heritage—rejecting official protection to preserve authenticity (Merrill).

- Communicative exploreres —they gather data on sites’ histories and conditions, discuss inclusive protection and commemoration; their actions fit the idea of communicative action in heritage.

- Performatives—adventure-seekers who craft their own narratives yet act ethically: they neither vandalize nor reveal locations. Their stance aligns with:

- Gender and accessibility: masculinist dominance—a promising starting point for further research (e.g., feminist urbex). As a physically demanding and often informal space, urbex can foster exclusion by gender and ability.

- Rhizomatic development: no center, spontaneity of experience.

Communities of explorers are far from uniform—their experiences and motivations depend on the type of exploration undertaken. Within urbex broadly understood, different variants and styles have emerged with differing risk levels, physical demands, ethics, and documentation methods. These shape not only modes of contact with space but also the identities explorers build and the relations formed within micro-communities. Examples include: rurex, infiltration (active facilities), rooftopping, draining (water systems), cataphiles (catacombs), bunkering (bunkers and shelters), buildering (climbing façades), or industrial archaeology (scholarly study of industrial sites).

The subculture is a surprisingly large, culturally and socially complex group, highly creative in sharing experiences—through traditional publications and abundant audiovisual materials; explorers build forums, social media groups, maps, and how-tos. Their activities often take on artistic and aesthetic dimensions, ranging to experiences that are sometimes extreme. Research literature offers varied approaches, including the aesthetics of contemporary ruins and in-between spaces, which Małgorzata Nieszczerzewska describes as a tension between ruinophilia and ruinophobia, and seeing the ruin as a process rather than a closed object. A key aspect is also forging a personal relationship with space that leads to intentional memory-work while avoiding formal recognition and institutional protection—often deliberately forgoing conservation or museum standards and accepting natural processes of decay as cultural value in itself.

In this perspective, urbex appears not as merely recreational activity but as an alternative, conscious form of participating in heritage. By accepting transience and ephemerality, explorers assign new value to places excluded from dominant narratives of the past. Building on analyses of individual experiences and community structures in urbex, we can see that urban exploration not only engages senses and emotions but also generates new forms of social relations and spatial memory. The next section considers urbex as a specific way of experiencing and co-creating cultural heritage.

URBEX AS CULTURAL HERITAGE

The main aim here is to view urbex from the perspective of cultural heritage—can this practice be included within that classification? Traditional approaches, increasingly contested today, fall within the Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD):

- UNESCO 1972 Convention, Art. 1 (tangible heritage): monuments, groups of buildings, and sites of outstanding universal historical, artistic, or scientific value.

- UNESCO 2003 Convention, Art. 2 (intangible heritage): practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, and skills recognized as part of cultural heritage.

- UNESCO Infokit 2011—What is Intangible Cultural Heritage: features of ICH: traditional, contemporary and living; inclusive; representative; community-based.

- Polish Heritage Protection Act (2003), Art. 3: a monument is an immovable or movable object that is testimony to a bygone era of historical, artistic, or scientific value.

These definitions indicate that urbex meets many conditions that could allow its recognition as a form of cultural heritage—especially regarding practitioners’ practices, knowledge, and experiences, as well as multi-disciplinary scholarly engagement. The sites explored often have historical or scientific value even if they are not formally listed as monuments. Knowledge about urbex is transmitted informally and builds a community identity, similar to other forms of intangible heritage. The practice is contemporary and unfolds across different cultural environments—meeting UNESCO’s criteria. Urbex practitioners document and popularize knowledge about visited sites, playing a role akin to heritage institutions—albeit outside formal legal frameworks.

Yet we also confront major simplifications and exclusions in traditional definitions. Here critical heritage studies enter the discourse—a research current since the 1990s that posits heritage is not objective or neutral but political, socially constructed, and often exclusionary. Heritage is not a “thing” but a set of practices and social relations that confer meaning on objects and spaces. Critical studies emphasize bottom-up heritage—created and practiced by communities rather than institutions. They also revalue difficult, non-obvious forms of heritage, such as urbex. Not all heritage is consensual, safe, and shared; it is often the product of struggles for representation, voice, and visibility, and a source of identity and political tensions. “Lynn Meskell conceptualizes negative heritage as a site of conflict, a repository of traumatic memory—serving positive educational ends or, conversely, being erased when it resists incorporation into collective memory“26. Urbex grapples squarely with such an understanding.

An archaeological perspective is also worth noting: fieldwork experiences have underpinned new, critical views of heritage. Urbex is an excellent example of combining field practice with theory, fitting this new mode of thinking. Drawing on the “turn to things,” urbex reassigns meanings to forgotten objects—especially visible in artistic photography of abandoned spaces. In short, urbex intersects with multiple threads in critical heritage studies, showing that such an approach is both justified and worth further exploration. “Heritage is no longer primarily ‘about the past’ as traditional approaches to monuments and ruins would have it; rather, it is oriented above all toward the future.”

From the perspective of the individual explorer, Weronika Pokojska’s “Forgotten Heritage” underscores the subjective character of perceiving heritage: we maintain a selective attitude toward what we acknowledge as heritage. We tend not to see—or not want to see—objects that are historically ambiguous or difficult, and those that are seemingly ordinary. We also omit, for practical reasons, places that are hard to access—far from marked parking areas and trails. These are precisely the spaces that become especially attractive to explorers, who, at considerable expense of time and resources, reach places ignored by the official circuit. For each urbexer, it is a unique, deeply personal experience.

Thus, urbex emerges as a particularly compelling and complex form of cultural experience with enormous potential to join the broad, inclusive group of phenomena called heritage in the sense used by critical studies. It aligns with entropic heritage, where natural processes of decay and transience are valued in themselves—without the need for formal conservation or restoration. Alternatively, urbex reflects alternative heritage, consciously rejecting official protection models and embracing bottom-up, informal ways of treating places as culturally valuable.

Explorers also participate in the bottom-up process of place-meaning—through personal experiences, narratives, and documentation, they assign new cultural identities to spaces regardless of institutional classifications. A special role here is played by the sensory and emotional experience of space, including the sounds and silence of post-industrial sites which—Jeffrey Benjamin shows—can become important artifacts of intangible heritage.

Recent research offers many useful lenses: Pablo Arboleda distinguishes performative explorers—focused on experience and adventure—from communicative ones—who document and disseminate knowledge (“Heritage Views through Urban Exploration“). Hilary Orange points to memory-work in post-industrial spaces, where exploration becomes a form of informal archiving (“Reanimating Industrial Spaces“). Małgorzata Nieszczerzewska emphasizes the ambivalence of ruin aesthetics—beauty and horror, attraction and repulsion (“Derelict Architecture“). Alice Mah sees ruin as a socio-cultural process entwined with local identity and economic change (“Industrial Ruination, Community, and Place“). These approaches show urbex as a practice of reclaiming forgotten places and actively co-creating new meanings for them. In the context of critical heritage studies, urbex appears not as marginal but as a fully fledged form of cultural reflection and alternative participation in heritage.

SUMMARY

Summing up the urbex experience makes its complexity clear—from individual motivations (authenticity and the desire to experience place without curatorial interpretation, curiosity, documentation, reflection), the various forms of exploration, the transience and fragmentariness of sites, through the conscious aestheticization of destruction and internal contradictions in the fascination with decay, to conflicts with law and social norms.

Urbex emerges as a multifaceted practice that transcends traditional understandings of urban exploration and enters into dialogue with categories of cultural heritage. It combines sensory experience, individual reflection, the creation of ephemeral communities, and critique of dominant models of urbanization and spatial control. It redefines heritage by emphasizing natural processes of decay, grassroots narratives, and the sensory experience of space—including sounds and silence as elements of intangible artifacts. Future research may focus on digitizing heritage, using VR to document ephemeral spaces, and reflecting on increasing commodification and spectacularization of exploratory practices. Urbex not only records transience; it becomes an active way of experiencing, reinterpreting, and safeguarding the ephemeral, opening new possibilities for contemporary understandings of culture and heritage.

From the viewpoint of critical heritage studies, urbex not only can but should be considered a form of cultural heritage. In modern framings, heritage is not merely a set of protected objects but primarily a dynamic social practice—a performative and negotiable process of assigning meanings to places. The category of heritage as action, developed in Anglophone literature and Polish heritology, shifts the focus from the question of whether something is heritage to how and by whom it becomes heritage. Urbex fits this frame perfectly: a bottom-up, ephemeral, and often contestatory way of practicing spatial memory outside official institutions. Explorers not only document ruins but reinterpret their histories, assign new meanings through embodied, sensory experience, and form communities resisting dominant culture. In this sense, urbex can be read as alternative heritage: non-canonical, unregistered, immeasurable—but real, enacted in practice and open to the future.

POTENTIAL RESEARCH AREAS

A still under-recognized thread is gender and accessibility. Carrie Mott and Sue Roberts point to the dominance of masculinist patterns in this subculture—exploration is associated with courage, risk, and physical strength, culturally coded as “male.” Women, non-binary people, and people with disabilities face physical and social barriers. A feminist perspective could expose mechanisms of exclusion and propose alternative strategies of exploration grounded in cooperation and relationality.

Another promising direction is analyzing cultural differences in treating ruins—from romanticism and aestheticization in the West to pragmatism, taboo, or rebuilding in other contexts (e.g., China, Japan, Latin America). Comparative research could reveal local valuation modes and memory narratives.

Urbex may also be treated as a metaphor for spatial exclusion—abandoned places often bear witness to social marginalization, economic decline, and inequality; exploring them becomes not only an aesthetic act but also a critique of urban policies and gentrification.

Finally, new technologies—VR, 3D scanning, digital sound archives—are gaining importance in documenting ephemeral heritage. They can not only preserve experiences but also create new, digital forms of memory and access to places that no longer exist physically or are unreachable to most (e.g., Mission: ISS—a virtual visit to the International Space Station by Meta Quest).

bibliography

- Apel, Dora. „Beautiful Terrible Ruins”, b.d.

- Arboleda, Pablo. „Heritage Views through Urban Exploration: The Case of ‘Abandoned Berlin’”. International Journal of Heritage Studies 22, no 5 (27 May 2016): 368–81.

- Audin, Dr Judith. „Open Call for Participation Research Network on Urban Ruins in Contemporary China”.Hong Kong, b.d.

- Bennett, Luke. „Bunkerology – A Case Study in the Theory and Practice of Urban Exploration”. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29, nr 3 (June 2011)

- Bingham, Kevin P. An Ethnography of Urban Exploration: Unpacking Heterotopic Social Space. Cham:Springer International Publishing, 2020.

- Ian Border, Ian, Joe Kerr, Jane Rendell. „The Unknown City: Contesting Architecture and Social Space”, The MIT Press, 2000

- Chapman, Jeff. Access All Areas: A User’s Guide to the Art of Urban Exploration. 4. ed. Toronto: Infilpress, 2005.

- DeSilvey Caitlin. „Observed Decay: Telling Stories with Mutable Things”, Journal of Material Culture, 2006

- Dicks Bella. „Encoding and Decoding the People: Circuits of Communication at a Local Heritage Museum” w European Journal of Communication, March 2000

- Dodge, Martin i Kitchin, Rob. „Exposing the Secret City: Urban Exploration as ‘Space Hacking’”.

- Gates Moses. „Hidden Cities: Travels to the Secret Corners of the World’s Great Metropolises: a Memoir of Urban Exploration”, 2013

- Garrett, Bradley L. „Undertaking Recreational Trespass: Urban Exploration and Infiltration”. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39, no 1 (January 2014).

- Glover, Troy D., i Erin K. Sharpe, red. Leisure Communities: Rethinking Mutuality, Collective Identity and Belonging in the New Century. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021.

- Harrison, Rodney. “Heritage as Social Action,” n.d.

- Kindynis, Theo. „Urban Exploration: From Subterranea to Spectacle”. British Journal of Criminology, 6 maj 2016,

- Mah, Alice. Industrial Ruination, Community, and Place: Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012.

- Merrill Samuel. „Keeping it real? Subcultural graffiti, street art, heritage and authenticity”, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2015 Vol. 21, No. 4, 369–389

- Mott, Carrie, i Susan M. Roberts. „Not Everyone Has (the) Balls: Urban Exploration and the Persistence of Masculinist Geography: Not Everyone Has (the) Balls”. Antipode 46, no 1 (styczeń 2014).

- Nieszczerzewska, Małgorzata. „Derelict Architecture: Aesthetics of an Unaesthetic Space”, b.d.

- Orange, Hilary, red. Reanimating Industrial Spaces: Conducting Memory Work in Post-Industrial Societies. Publications of the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, Volume 66. London: Routledge,2016; Benjamin, Jeffrey Rozdział 5: „Reanimating Industrial Spaces: Conducting Memory Work in Post-Industrial Societies” s.108

- Orbuch, Terri L. „People’s Accounts Count: The Sociology of Accounts”. Annual Review of Sociology 23, no 1 (sierpień 1997)

- Rosen, Michael J. „Place Hacking : Venturing off Limits”, 2015

- Pokojska, Weronika. „Zapomniane dziedzictwo, czyli urban exploring”. Case studies, 2015.

- Schönle, Andreas i Julia Fauci. Architecture of Oblivion: Ruins and Historical Consciousness in Modern Russia. DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2011

- Shepard, Wade. „Ghost Cities of China: The Story of Cities without People in the World’s Most Populated Country”, 2013

- Stobiecka, Monika (red.) „Krytyczne studia nad dziedzictwem. Pojęcia, metody, teorie i perspektywy”, Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2023

Leave a comment